The judo legend became involved in the sport as a youngster when his parents wanted their children to connect with their Japanese culture

By Evan Lasseter

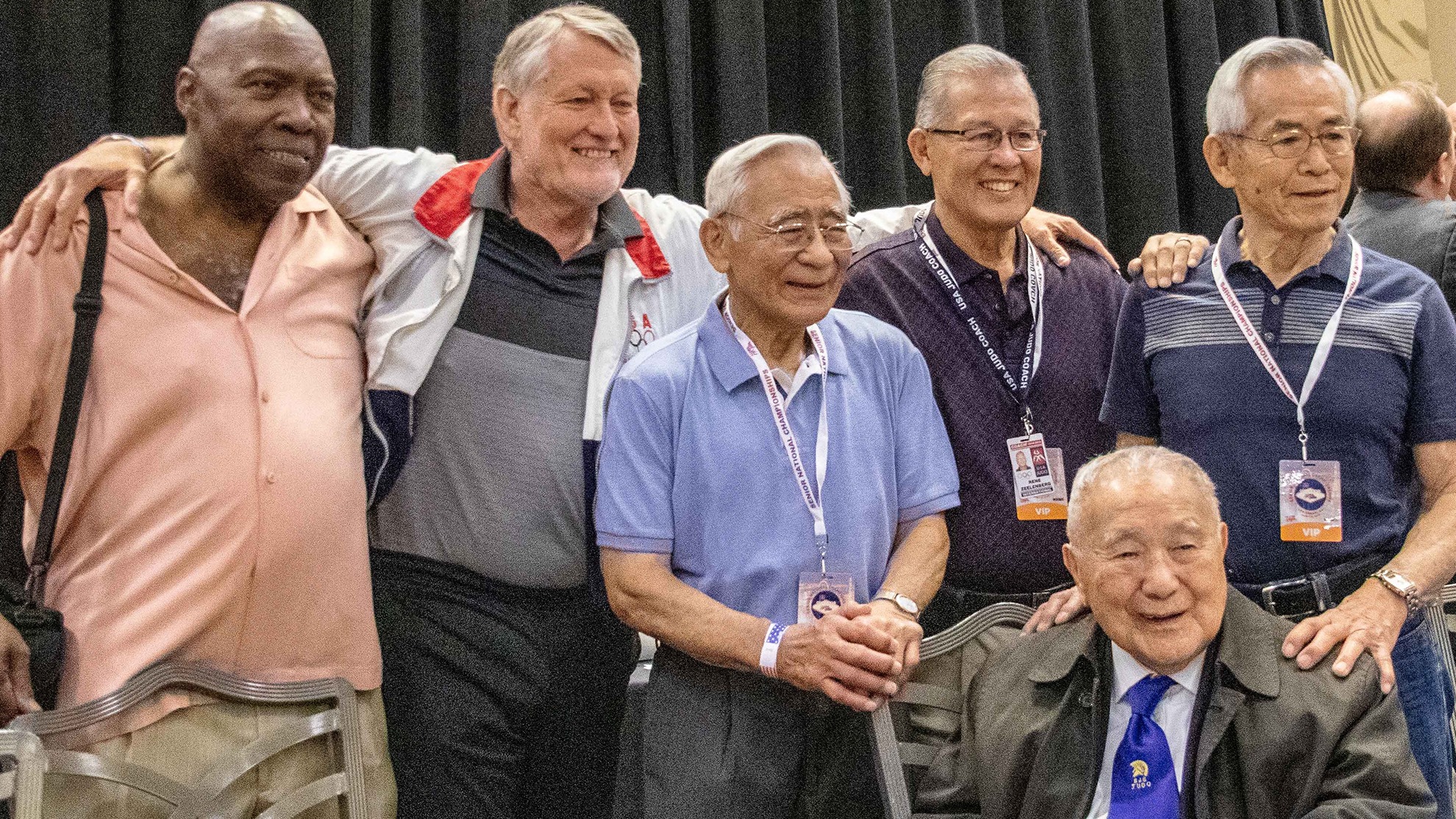

When Marti Malloy won the bronze medal in judo at the London 2012 Olympic Games, Yoshihiro Uchida, then 92, was in the stands.

Malloy presented Uchida with the Order of Ikkos award that U.S. Olympic medalists present to one person who coached and supported them in their Olympic journey.

“For me it wasn’t even a question, you have to think of the person who influenced you, and supported you, and sacrificed for you,” Malloy said. “And when you add those things up, there is only one person that kind of comes to mind in that scenario.”

Malloy trained for the Olympics with Uchida at San Jose State University, where the two cultivated a connection as coach and student starting in 2004.

Judo has been a lifelong endeavor for Uchida, who celebrates his 100th birthday on April 1. He was the United States coach when judo made its Olympic debut at Tokyo 1964.

“To be honest, it took me over the years to realize his influence and history, and how impactful he has been in so many ways,” Malloy said. “But to me he has become like a grandfather, with my support system early on. We’ve had all these great successes together and we really do care about each other.”

Uchida’s judo journey started in Garden Grove, California, where he was the son of Issei, first-generation Japanese immigrants to North America. Uchida remembers his parents and other Japanese farmers in the area spending early mornings and long nights working.

Uchida remembers that when he was 10 years old, his parents were concerned their children were not learning enough about Japanese culture. They said the children “didn’t know anything about Japan,” Uchida said in an interview leading up a planned 100th birthday celebration.

Uchida’s parents began trying to connect their children to their heritage through various outlets, such as Japanese schooling. For Uchida, the outlet was judo, a martial art born in Japan in 1862.

Though he wasn’t a natural at first, Uchida and his brothers would come home and talk about judo. Judo became more than just a martial art, also teaching life lessons to a young Uchida.

“At that time we didn’t know what it was to be defeated,” Uchida said. “That is one thing I learned, that you don’t blame it on anyone else, you blame it on yourself. And you want to improve and become stronger.”

Uchida’s parents were forced into internment camps during World War II. Two decades later, when judo debuted as an official Olympic sport in Japan, Uchida returned to his parents’ native country as coach of the U.S. Olympic Judo Team.

Under Uchida’s guidance, the middleweight James Bregman became the first American to win an Olympic medal in judo, earning the bronze in Tokyo. Forty-eight years later, Malloy earned bronze in London.

“The thing about him is that he’s been consistent for so long,” Malloy said of Uchida. “He hasn’t gone from priority to priority. It’s always been about using judo to build good people.”

Along with Henry Stone and others, Uchida worked to establish judo as an official Olympic sport.

Stone was at the University of California-Berkeley while Uchida was at San Jose State University. The two organized a judo tournament competing against each other. The tournament marked the first time San Jose State’s judokas fought competitively, Uchida said, and made for a tough matchup against Stone’s stronger athletes.

“Henry Stone’s University of California fellas were much stronger because they had judo,” Uchida said. “Ours had judo but not in a competitive way.”

Uchida relied on Stone, the wrestling coach at Cal, for help when developing judo competitively to present to the Amateur Athletic Union. The men established weight classes that made judo competitive and fair.

“The Isseis didn’t know anything about the Amateur Athletic Union,” Uchida said. “So we were very fortunate in having a man, Henry Stone, who understood both wrestling, boxing and all these sports that the colleges played.”

After the AAU recognized judo as a sport, the organization recommended it become an official Olympic sport, Uchida said.

Uchida earned a degree in biological science from San Jose State. The Judo program Uchida built there, over seven-plus decades of coaching, has produced more than 20 Olympic coaches and athletes since 1964.

San Jose State was ground zero for the relationships Uchida built with his most recent Olympians in Malloy and Colton Brown, who competed in the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympic Games. Both Olympians trained under Uchida as students at San Jose State.

Malloy now lives in San Jose State to remain close to judo. Uchida still attends practice, teaches the new freshmen and speaks to coaches on a regular basis, Malloy said.

Just as judo was an outlet that taught Uchida life lessons as a young man, his coaching extended beyond just martial arts. Uchida wanted judo to be a vessel for “creating better relationships” around the world.

“He knew when we were working hard or not working hard, and he always wanted to keep the motivation high,” Malloy said. “But he really wanted us to be functioning members of society.”

Evan Lasseter is a student in the Grady Sports Media program at the University of Georgia, which is partnering with the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Museum to produce content this semester.