Betty Robinson won the first-ever Olympic women’s track and field race and recovered from a near-fatal to plane crash to win another gold eight years later

Betty Robinson made a name for herself by winning the gold medal in the first-ever women’s Olympic track and field race, the 100-meter dash at the Amsterdam 1928 Olympic Games. Eight years later, Robinson again made headlines, recovering from a near-fatal plane crash to win Olympic gold in the 4×100-meter relay at Berlin 1936.

For more than half a century, though, those gold medals largely stayed tucked away in a candy box, first in Robinson’s closet and later in her daughter’s jewelry box in the back of her closet, retrieved only when the time was right to show guests.

“When I was growing up, as far back as I can remember, they were never displayed, there wasn’t a lot of talk about them. If somebody wanted to see her medals, they were in the linen closet, on the second shelf in the back,” said Jaine Hamilton, Robinson’s daughter, who took possession of the medals after her mother passed away in 1999. “They never made a big deal out of it. I guess it was a humility of sorts.”

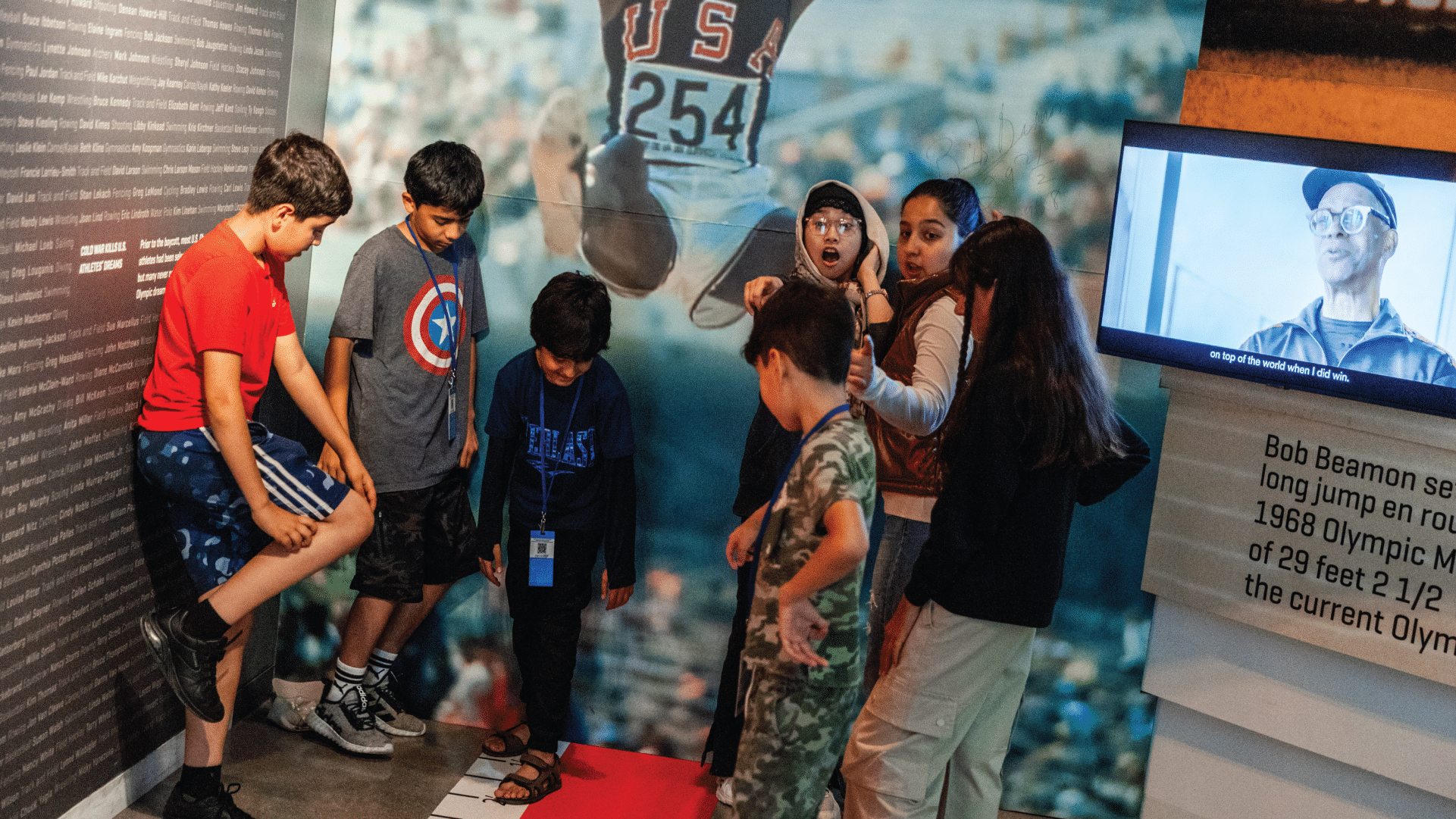

Soon, though, Robinson’s gold medals will be on display for all to see. Hamilton recently visited Colorado Springs to loan her mother’s medals and other memorabilia to the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Museum that will open later this year.

“This is the first time I’ve been without these medals in so many years,” said Hamilton, noting that the medals traveled with her to live in five different states. “But it seemed like the right thing to do. I am totally excited about the Museum.”

Hamilton said that for the longest time, a chocolate-covered mint candy in a wax wrapper remained in the candy box with the medals. It was not until a few years ago that she decided to throw out the candy and place the medals in protective plastic. The 1928 gold medal has a chain attached to it so that when necessary, her mother could wear it around her neck.

“Maybe the candy was keeping the medals safe,” Hamilton said. “It always fascinated me that somewhere along the line, a thin mint had gotten in that box and stayed in it.”

Betty Robinson blazed her way into the history books, first attracting attention as a high school sophomore chasing down a train. That led to a spot on her high school’s boys track team — the school did not field a girls track team – and subsequently a trip to Amsterdam 1928, where Robinson won gold in the 100 and a silver in the 4×100 relay.

Robinson missed the Los Angeles 1932 Olympic Games after nearly dying in a plane crash the previous year when rescuers originally presumed she was dead. She spent 11 weeks in a coma and was told she would never again walk without a limp, let alone run.

But if you told Betty Robinson she cannot do something – such as run — that only strengthened her resolve. Even though she could no longer get into a runner’s crouch for the start of a race, Robinson did recover to run. She ran the third leg of the 4×100 relay at Berlin 1936 and when Helen Stephens ran the anchor leg to take the United States to gold, Robinson was ecstatic.

It was not much different than when Robinson was 81 years old and – ever the thrill seeker with a need for speed — insisted on riding the roller coasters at the Six Flags Great America amusement park. Or when she was 84 and carried the Olympic Flame during the Atlanta 1996 Olympic Games Torch Relay.

“The first [gold] medal was not as important to her as her ’36 medal,” Hamilton said. “The first was easier; the second she had to work her tail off to get back from injury. My uncle would ride a truck on the track while she ran and he could hear the pin clicking in her knee while she was rehabbing. It had to have been pretty painful as she got back to running. She carried the scars from the hard work she did.”