Race car driver Geoff Bodine’s keen interest in helping Team USA propelled the U.S. to its first Olympic bobsled gold in half a century

By Josh Barr and Chase McCleary

Team USA was a bobsled powerhouse right out of the gate. They won gold and silver at the St. Moritz 1928 Olympic Winter Games, the second Winter Games, and went on to receive another six medals in total over the next five Games, half of which were gold. However, following their bronze-winning race in 1956, the U.S. Olympic Bobsled teams wouldn’t see the podium, much less the top, for another 46 years.

A commitment to build top-notch bobsleds for American racers

While watching another struggling American bobsled performance at the Albertville 1992 Olympic Winter Games, Geoff Bodine decided enough was enough.

Bodine, a former NASCAR driver and winner of the 1986 Daytona 500, visited the team in Lake Placid to investigate. He was appalled to find athletes using substandard, imported sleds from Europe. “When I heard that our athletes weren’t using American-made bobsleds, that was unacceptable,” said Bodine. “We are Americans. We have technology. We can do better than this.”

Relying on his NASCAR prowess and network, Bodine founded the Bo-Dyn Bobsled Project with Bob Cuneo, owner of Chassis Dynamics (thus Bo-Dyn) in 1992, which began constructing higher quality equipment free-of-charge for the American athletes.

The unveiling of the fastest bobsled in the world, the “Night Train”

With Bo-Dyn technology, the U.S. won silver and bronze for the four-man race in 2002 but still lacked that little something extra to top the podium. After another eight years of cutting-edge innovation and development, the Bo-Dyn Bobsled Project unveiled “Night Train,” a $250,000 state-of-the-art American-made bobsled. Dubbed the fastest sled in the world, it was poised for greatness.

The name was first written on the back of a barroom napkin after the bobsled’s testing. Among the prototypes presented, the team immediately preferred the sharp, jet-black design, and without enough time to paint the bobsled before competition, the team named it “Night Train.”

Bodine, Cuneo, and their team knew little about bobsled making. “We had to learn to build them, what made them go fast, what the athletes liked and what they didn’t like,” said Cuneo. Implementing technologies used by NASCAR, Bo-Dyn Bobsled spent endless hours designing, testing, and innovating. They used Kevlar, fiberglass, and a specialized carbon-fiber composite to optimize aero dynamicity and weight-distribution of the bobsleds. These advancements proved so successful that European teams began bidding for the sleds, a complete turn-of-the-table from the imported European sleds of the early ’90’s.

Bodine refused. “The money was dangled out in front of us to see if we would cave in and sell some of our equipment, but we said no,” said Bodine. “We didn’t do it for profit. We did it for our American athletes and no one else.”

Bobsledding is an infamously dangerous sport. The track at the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games faced serious criticism going into the Games following the tragic crash of Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili, who died only hours before the Opening Ceremony. Incredibly fast speeds and sharp turns led to several crashes, six during the four-man heat alone.

To make matters more complicated, Night Train pilot, Steven Holcomb, had been battling the degenerative eye disease Keratoconus for years prior. In 2008, only two years before competition, he underwent an intensive corneal surgery that inserted corrective lenses into his eyes.

The Bo-Dyn Project brings Team USA to the pinnacle of bobsledding

Nevertheless, in 2010, the U.S. Olympic Men’s Bobsled Team won its first gold medal since 1948, ending a 62-year drought with a win over the five-time, gold medal-winning German team by a mere 0.38 seconds. Holcomb established himself as one many consider to be the greatest bobsledder in U.S. history.

The push team included Justin Olsen, a New York Army National Guardsman, Steve Mesler, an inductee of the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and CEO of Classroom Champions, and Curt Tomasevicz, a biological systems engineering PhD and middle linebacker for the University of Nebraska Cornhuskers.

“We’ve worked so hard and gone through so much in the last four years. To end on a high note like this is huge. It’s overwhelming,” said Holcomb.

“I didn’t get a trophy, and I didn’t get any money for it, but seeing those gold medals hanging on those four athletes felt pretty darn good,” said Bodine.

Thanks to continued efforts by Bo-Dyn Bobsled Project Inc, a new and improved “Night Train 2” premiered at the Sochi 2014 Games and won a silver medal in the four-man bobsled. Though originally winning bronze, the team was upgraded following doping revelations against Russian bobsledder Alexander Zubkov.

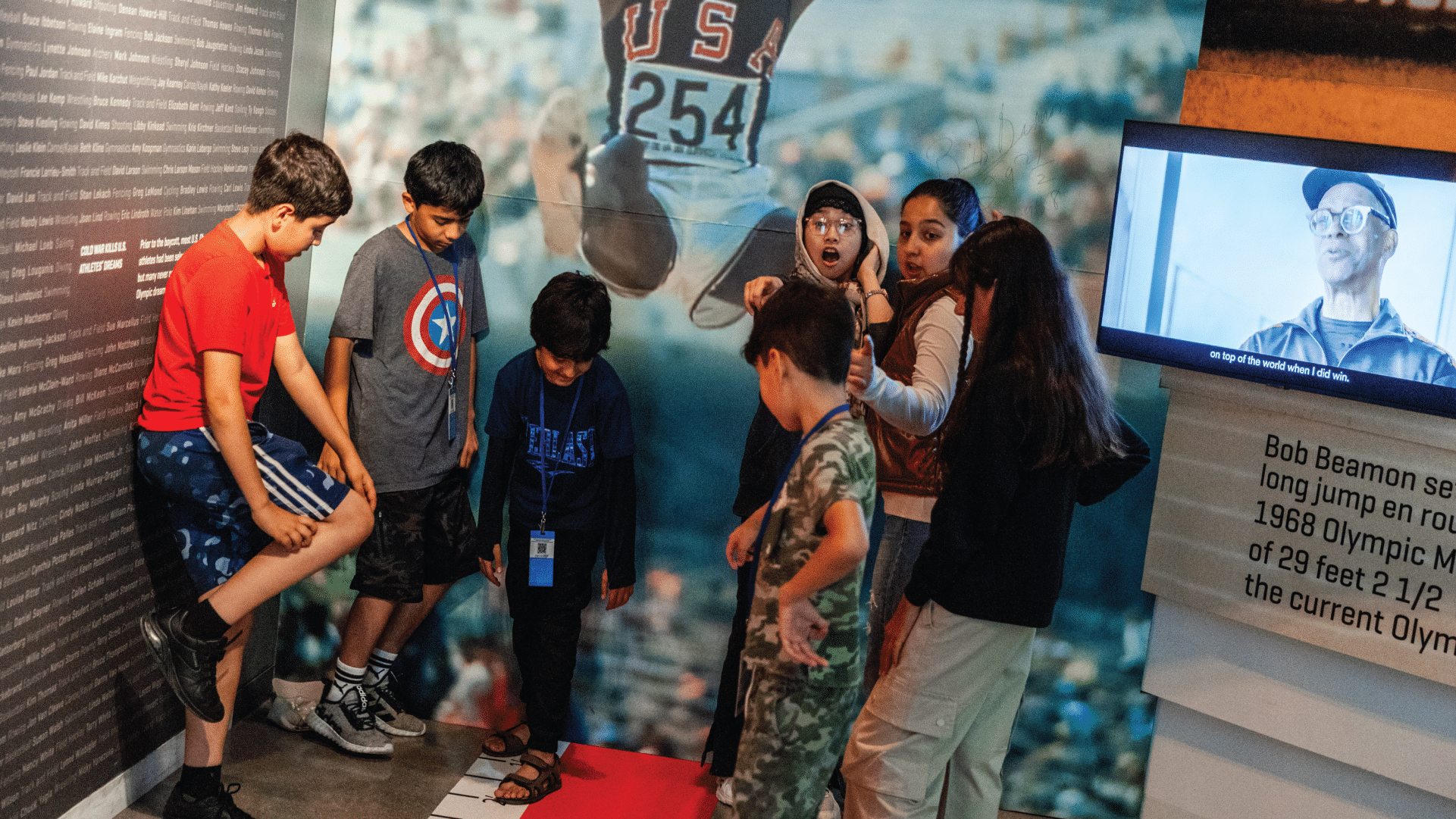

The original Night Train bobsled, as well as Steven Holcomb’s 2010 bobsled uniform and medals, are currently on display at the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Museum in Colorado Springs, Colorado.