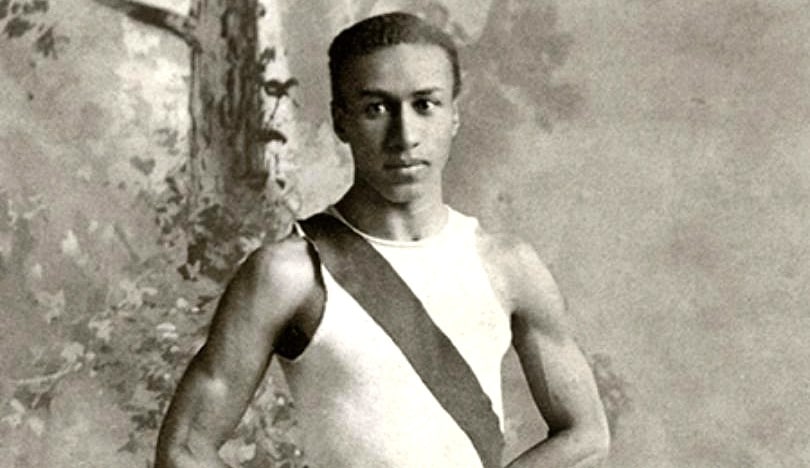

The standout runner from Wisconsin won two bronze medals at the St. Louis 1904 Olympic Games

Although he had already compiled a substantial resume, there was not much fanfare when George Poage traveled to the St. Louis 1904 Olympic Games. In high school, Poage had been salutatorian of his class and the third Black student to graduate from La Crosse High along the Wisconsin-Minnesota border. At the University of Wisconsin, Poage became the first Black athlete to win a race in the Big Ten Conference track championships and he graduated with a degree in history.

But as the 23-year-old Poage traveled to St. Louis, there was little anticipation that Poage would become the first Black American to win an Olympic medal. Nor was there a sense that this would be quite an achievement.

Of course, that could also be attributed to the fact that the first few versions of the modern Olympics were far from the Games of the 21st century. At the time, the St. Louis Games were held in concert with the Louisiana Purchase Exposition – which became better known as the World’s Fair – and took place over the course of nearly five months. Only 12 nations were represented and just 62 athletes came from outside North America. (The Games were originally awarded to Chicago before being moved to St. Louis after organizers there threatened to upstage the Chicago event with their own event.)

Also, several top Black athletes chose not to participate. American civil rights leaders urged Black athletes to boycott the Olympics because fans attending events would be segregated. Poage, though, seemed to feel it would make a bigger statement to participate, competing in four events.

While he did not medal in the 60-meter dash or the 400-meter run, Poage placed third in both the 200-meter hurdles and 400-meter hurdles, winning two bronze medals and indeed becoming the first Black American Olympic medalist.

Following the St. Louis Games, Poage stayed in St. Louis as a high school principal and then as a teacher at the Charles Sumner High School, the first school west of the Mississippi River exclusively for Black students. Ten years later, Poage moved to Minnesota and later to Chicago, where he first worked in a restaurant and then spent 30 years as a clerk for the U.S. Postal Service, according to the La Crosse County Historical Society. Poage retired in 1953 and died in 1962 at age 81.

It was not until more than 50 years later that Poage’s accomplishments finally were celebrated.

“It’s one of those things that the story just was forgotten,” said Steve Carlyon, the parks and recreation director for the City of La Crosse from 2007 to 2018. “Back then, it wasn’t in vogue to talk about Black Americans in the Olympics.”

Carlyon remembers being in shock while driving one day in 2012. He was tuned in to the local talk radio station in La Crosse – where callers often praised or critiqued city doings – when the subject was the London 2012 Olympic Games. A listener called in and – following up on a letter to the editor in the La Crosse Tribune — wondered why the city had not done anything to honor one of its most accomplished natives, George Poage.

It was a legitimate question, Carlyon thought to himself, even though he previously was unaware of who Poage was, what Poage had done or where Poage was from.

Carylon did some research and learned about Poage. Carlyon had tried unsuccessfully to change the name of Hood Park, an older park in a struggling part of La Crosse. What if they could rebuild the park with top-of-the-line amenities and rename it in honor of the first Black American to win an Olympic medal? Carlyon commissioned local historian Margaret Lichter to prepare a report on Poage, hopeful it would help sway public opinion.

“It had to go through lots of layers of approval, but there was enormous support for it,” Lichter said. “The timing was certainly right. There was quite a bit of surprise the community hadn’t done anything for him, but he doesn’t have family here any longer.

“The community certainly rallied. It was more a sense of, ‘How could we have forgotten this?’ ”

Current La Crosse Mayor Tim Kabat, a native of the city, was among those who previously were unaware that Poage was from La Crosse. “I was very surprised and very proud that we had a citizen of our fair city that was a part of” history, Kabat said. “Very cool.”

The $1.4 million renovation included new playground equipment, a shelter and a huge splash pad, as well as a sculpture of Poage. In the winter, park officials turn a field into an ice skating rink. There also is a storyboard prepared by Lichter, chronicling Poage’s life, from being born in Hannibal, Missouri, to relocating in La Crosse, where his parents worked for and lived with some of the wealthiest families in town. Poage and his older sister, Nellie, had the benefit of being educated; they were the second and third Black students to graduate from La Crosse High.

Race was a topic that seemed of note to George Poage. His high school salutatorian speech was titled A Civil Phase of the Race Problem. His college senior thesis was on An Investigation into the Economic Condition of the Negro in the State of Georgia During the Period 1860-1900.

After graduating high school, Poage continued his success at the University of Wisconsin, even filling in as the coach of the track team when the regular coach had to go out of town. Poage’s victories on the track earned an invitation to compete for the Milwaukee Athletic Club’s track and field team and a trip to the St. Louis Olympics. Yet after his athletic career, Poage retreated from the spotlight.

David Waters, a recently retired professor at Viterbo University in La Crosse, and Bruce Mouser, a retired professor at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, spent considerable time researching Poage’s life to remember one of the greatest athletes in their city. Mouser wrote a book about Poage; it was Waters’ letter to the editor of the La Crosse Tribune that eventually caught Carlyon’s attention, spurring the idea for Poage Park, which has helped revitalize a neighborhood on the south side of La Crosse.

“At certain times, it just seems to be the right thing to do,” Waters said. “For children here to learn about a local runner, ‘Hey, boys and girls, you can do that too.’ ”