In everything he did, as a Olympic champion and in his professional life, the hurdler from Pennsylvania had specific goals

By Josh Barr

Update: Charlie Moore passed away on Thursday, October 8. He was 91.

Growing up in the Pennsylvania countryside west of Philadelphia, Charlie Moore yearned for the school day to end, so that he could go home and exercise his horses.

“That became my life,” Moore said. “I was mesmerized by working with the fox hunt and the hounds.”

Having horses, though, required money, Charles Hewes Moore Sr. reminded his son. Young Charlie needed to find a way to pay for the horses’ feed and care. Each year, Charlie raised a few hundred chickens, which he then slaughtered, packed and sold to his mother’s friends and their neighbors as friers.

“I always felt that my sense of responsibility came from those experiences,” said Moore, who celebrated his 91st birthday in August. “I got a special start in life with that experience.”

This sense of purpose carried throughout Moore’s life, from becoming an Olympic champion to a long career as a businessman, from serving on the board of directors of the U.S. Olympic Committee to working as the athletic director at his alma mater Cornell University, from serving as executive director of the Committee Encouraging Corporate Philanthropy to raising nine children and enjoying 16 grandchildren and one great grandchild.

Along the way, Moore authored two books: Running on Purpose: Winning Olympic Gold, Advancing Corporate Leadership and Creating Sustainable Value and One Hurdle at a Time: An Olympian’s Guide to Clearing Life’s Hurdles.

Listen: Charlie Moore talks about living with a purpose

Yes, Charlie Moore always had a purpose.

That’s how he went from being a young boy who did not participate in athletics until prep school to winning the gold medal in the 400-meter hurdles at the Helsinki 1952 Olympic Games.

Moore’s track career came as a bit of a surprise to Moore himself. While his father had been an alternate for the U.S. track and field team at the Paris 1924 Olympic Games, he had not pushed his son to compete until his junior year of high school. One day late in the summer of 1945, Charles Sr. – most often known as Crip – told his oldest son to grab his stuff, they were going for a ride.

“He took me for a long drive to the prep school he went to,” Charlie said.

When they arrived at Mercersburg Academy in south-central Pennsylvania, father and son did not go to the admissions office. They went straight to track coach Jimmy Curran, who had coached Crip Moore, Mercersburg class of 1922.

“Here, Jimmy, see what you can do with this boy,” Charles Moore said.

Crip had been a hurdler, so Curran decided to see if Charlie could hurdle too.

“I never hurdled or anything in my life,” Charlie said. “I guess I was a fast learner.”

By the time he graduated Mercersburg in 1947, Moore was an improved hurdler who had run on the prep school’s race-winning teams in the Penn Relays. With a high number of veterans returning from World War II taking up many of the admission slots at the larger public universities such as Penn State, Moore decided against going to one of the smaller Pennsylvania state colleges. He opted to go to Cornell University and compete for the Big Red. Studying engineering – a five-year program – had one other benefit, Crip Moore noticed. Enrolling in the fall of 1947, Charlie would be on track to graduate in the spring of 1952, a few months before the Helsinki 1952 Games.

“My father dreamed constantly about me making making the Olympic team,” Charlie Moore said. “It had not crossed my mind.”

While his father saw the potential to stay in college and continue to train, Charlie Moore was unsure of his standing when competing against top competition. When it came time for the 1948 AAU National Championships, Moore opted to compete in the junior division and not the seniors, which was the Olympic qualifier.

“I didn’t have particularly high confidence in how good I was,” Moore said. “I just thought I wasn’t ready. I wasn’t strong. I was just a scrawny kid. In hindsight, I could have made it and done very well.”

Instead, Moore went back to Cornell, won a few more NCAA and AAU national championships and refined his technique. While the standard was to take 15 steps between hurdles, Moore and his father discovered that he could cover the same ground in 13 steps, a realization that revolutionized the 400-meter hurdles.

“I had a long stride,” Moore said. “I knew you ought to be accelerating, not reducing speed over the hurdle. When I went to 13 steps, that was a big deal. I would do it for seven or eight hurdles and then I was so far ahead that it became more important to win the race, so why take a chance of hitting the hurdle? Then I would go 15 steps to the finish line.”

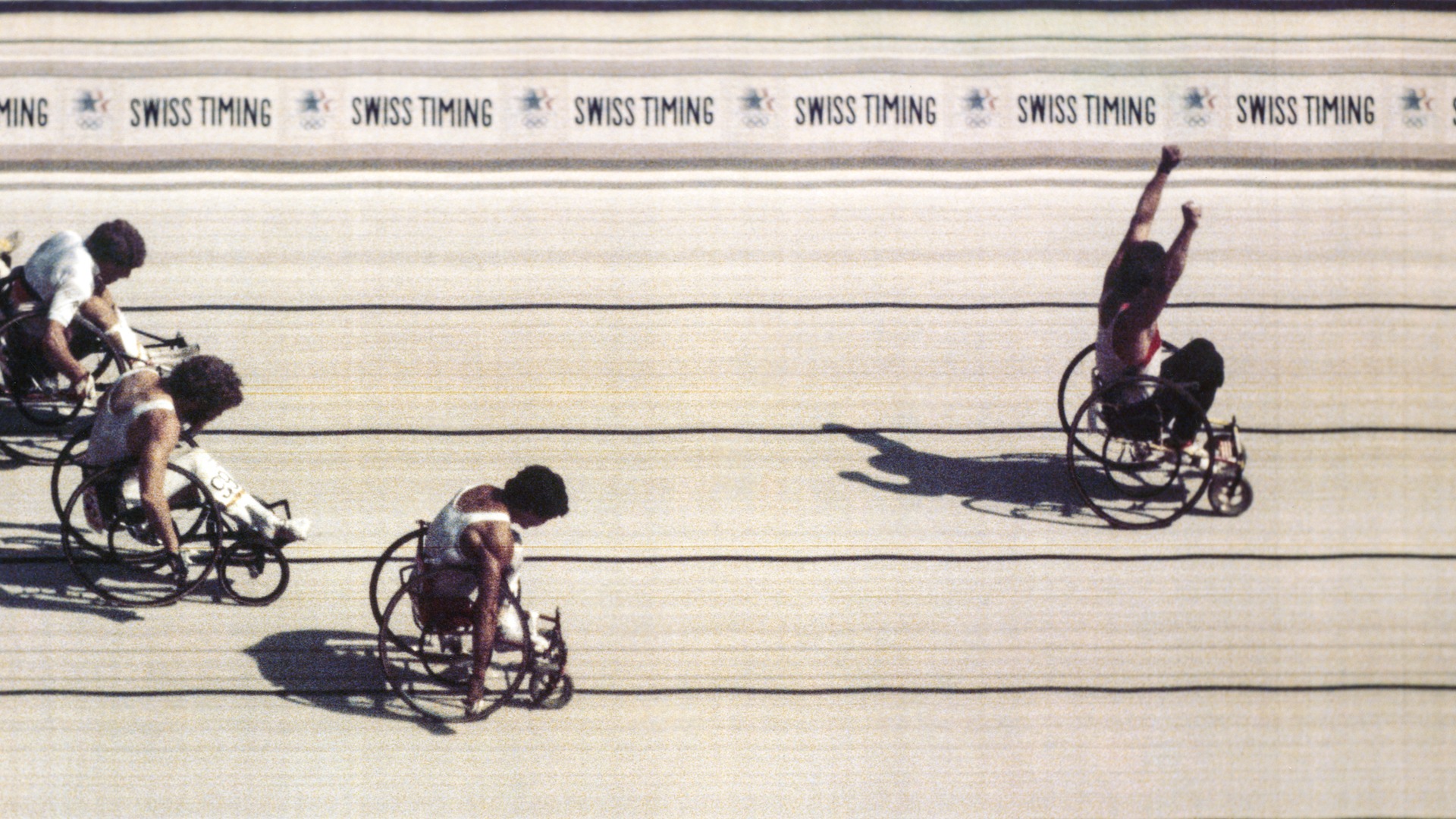

Moore qualified for the Helsinki Games by setting an American record of 50.7 seconds, one-tenth of a second off the world record. He believes he could have set the world record in the Olympic final, but backed off to ensure victory and win the gold medal in an Olympic-record 50.8 seconds. Moore also won silver in the 4×400-meter relay.

After the Games, Moore returned home and went into the family steel forging business. He briefly considered trying to run again before deciding that it would be nearly impossible to live up to the standard he had set.

“I went home and took those shoes, threw them away and never looked back,” he said.

While he did not run competitively again, Moore found that his training as an athlete made a big difference in his work as a businessman. He knew the determination, resilience and work ethic needed to succeed.

“They’re all easily transferable to your work environment,” Moore said.

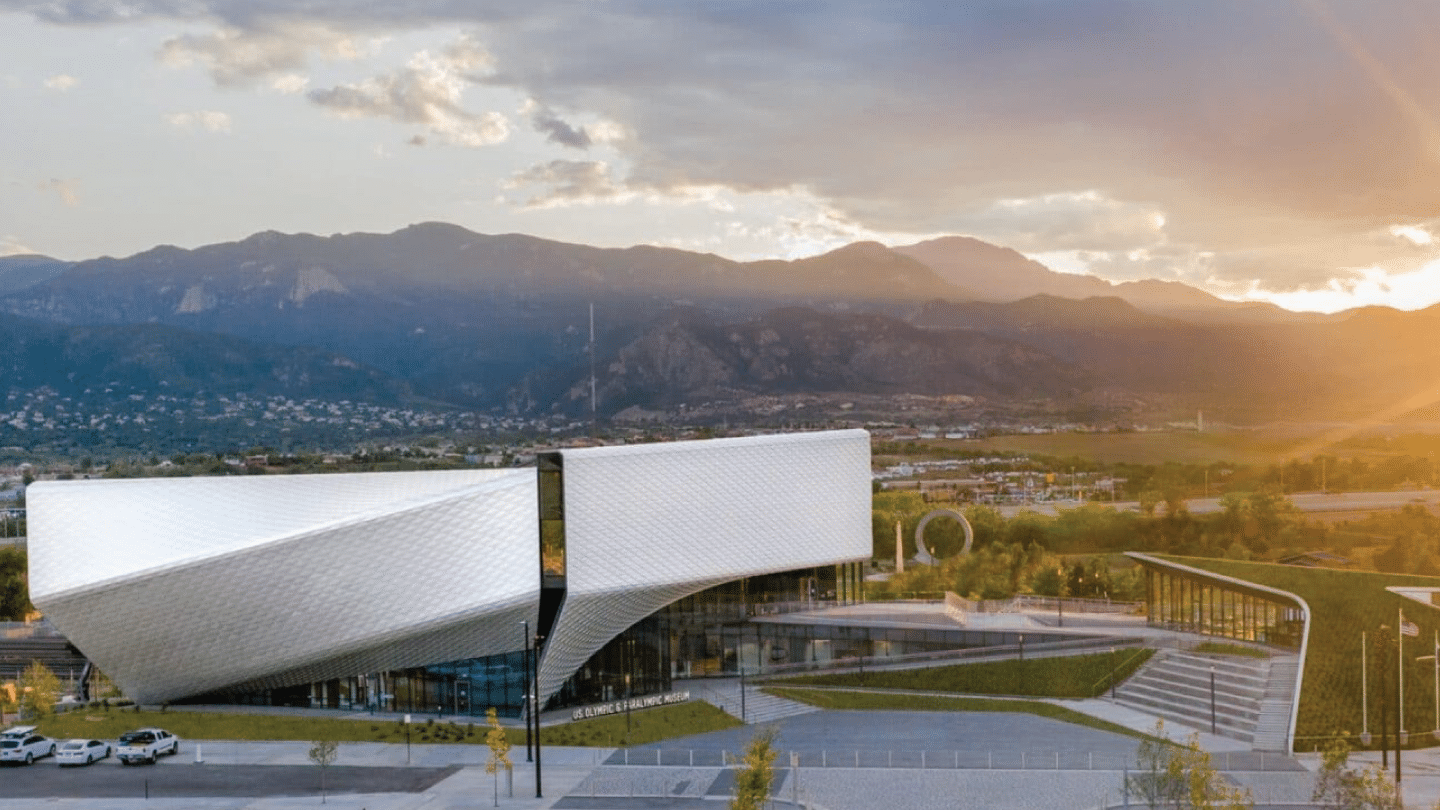

Even after he retired, Moore maintained that same philosophy. He worked to bring fiber-optic broadband to his hometown of Laporte, Pennsylvania, about an hour west of Wilkes-Barre in the north-central part of the state. He also pushed to find ways to train more emergency medical responders. At the 2019 U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Alumni Reunion, Moore joined Madeline Manning-Mims for an emotional StoryCorps conversation.

Along the way, Moore picked up fitness training in his late 60s and continued playing golf. He has one regret – never being able to shoot his age on the golf course. Moore had planned to take his entire family to the Paris 2024 Olympic Games, 100 years after his father was a Team USA alternate at the same site.

However, this past winter, fate intervened. Moore was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Moore could have opted for chemotherapy, but he declined because the cancer by then was non-operative and he and his family were concerned that treatment would negatively affect the quality of the rest of his life.

“I’ve had a great life,” Moore said. “I had a lot of things planned for myself beyond 2020, but really, I have no regrets. I’ve had a full, impactful life. What more could anyone ask?”