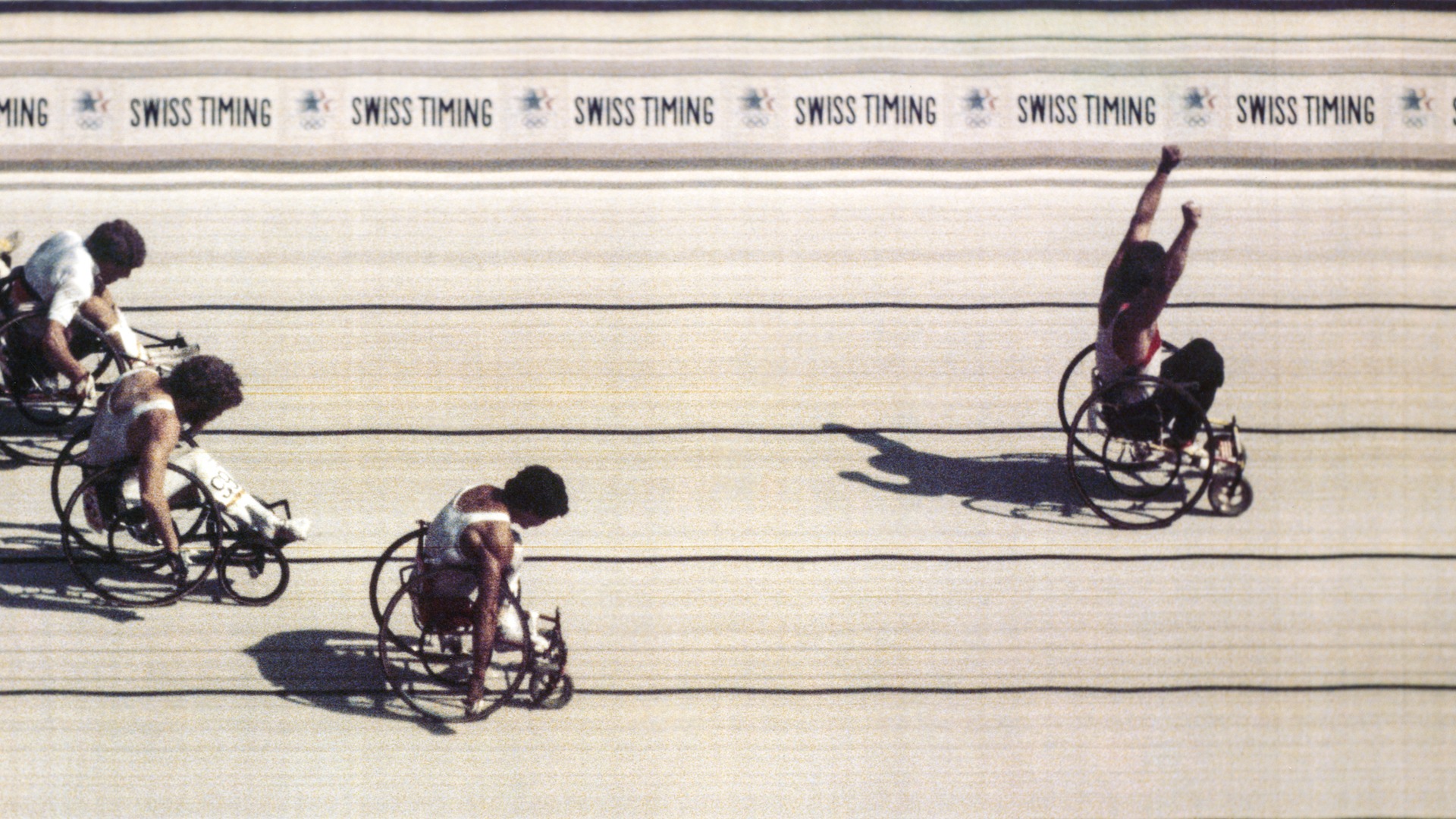

The 1998 U.S. Women’s Hockey Team won Olympic gold and sparked the sport’s growth throughout the country.

By Philip Hersh

Angela Ruggiero’s hockey story was typical for many girls of her generation. Growing up in suburban Los Angeles of the 1980s and early 1990s, she was the only girl on boys’ teams, dressing by herself in girls’ bathrooms at the rink, unable to see much of a hockey future for herself because the few U.S. colleges that had women’s teams at the time were all 3,000 miles to the east.

But when she was 12, Ruggiero got an unexpected opportunity, one that would change her life.

And Ruggiero, in turn, helped change the lives of thousands of girls and young women who followed because she seized on the chance that presented itself July 21, 1992 — the day the International Olympic Committee announced that women’s hockey had been added to the program for the Nagano 1998 Olympic Winter Games.

“It gave me a purpose,” Ruggiero said.

Ruggiero had her mind made up: she wanted to be an Olympian in hockey, her preferred sport of the many she played.

Nearly six years later, when Ruggiero, then a high school senior and the baby of the U.S. roster, and her teammates won the 1998 women’s hockey gold medal by defeating favored archrival Canada, 3-1 in the final, the eight-year-old Lamoureux twins, Jocelyne and Monique, saw snippets of the game while watching from home in Grand Forks, North Dakota. The Lamoureux girls had begun playing hockey only a couple years earlier — as girls on boys’ teams, just like Ruggiero — and suddenly they, too, had a purpose.

“Having an awareness at a young age we could be in The Olympics as female hockey players, it became a dream,” said Jocelyne, now Lamoureux-Davidson. “We wrote school projects about them because they won a gold medal.”

Twenty years later, a goal by Monique, now Lamoureux-Morando, would force overtime in the PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter Games gold-medal game against Canada. Jocelyne then scored the decisive shootout goal that gave Team USA its first women’s Olympic hockey title since 1998.

And, coming full circle, it was Ruggiero — an IOC member, Hockey Hall of Famer, national team player from age 15 and defenseman in the first four Olympic women’s hockey tournaments — who presented the 2018 team with its gold medals.

AJ Mleczko, a forward on the 1998 team, covered hockey at the 2018 Winter Games as an analyst for NBC sports, an opportunity she says owed to her having been an Olympian. Mleczko, like Ruggiero a Harvard graduate and player, now works about two dozen Islanders games as a studio analyst for MSG Network and last season became the first woman to work as in-booth analyst for an NHL postseason game on NBC.

“Our 1998 team certainly were trailblazers,” said Mleczko, mother of four hockey players (two girls, two boys), “but it wasn’t lost on us there had been trailblazers before us who almost nobody knows. We broke through a glass ceiling and really forged a path for the next generation.”

That path now has taken the 20 members of the 1998 gold medal team to selection in the Class of 2019 in the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Hall of Fame. They are Hall of Famers not only for winning but also for having an impact that has far outlasted the moment of triumph in Japan.

The team would be on a Wheaties box cover. Individual players would appear on the big TV talk shows of the era: Letterman, Leno, Rosie, Regis and Kathie Lee. And, perhaps even more importantly, they would appear on high school stages, inspiring young girls the way Lisa Brown-Miller, the 1998 team’s doyenne at age 31, did the Davidsons with a speech in Grand Forks.

“Without that gold medal, without that team, there is no way women’s hockey would be where it is today,” Lamoureux-Davidson said.

At the time of the Nagano 1998 Olympic Winter Games, women’s hockey still was two seasons away from becoming an NCAA championship sport. There were just 14 Division I teams in 1997-98, and the University of Minnesota had the only one outside New England or New York state. In the 2019-2020 season, there are 41 teams eligible for the NCAA championship, 36 in Division I and 11 west of New York State.

All but one of the 20 women on the 1998 U.S. Olympic hockey roster played (or, in Ruggiero’s case, would play) at colleges in the six New England states. Fifteen of the 23 members on the 2018 roster played at colleges west of New York State.

The growth of college women’s hockey in the United States also had a big impact on opportunities for Canada’s women. Its 1998 Olympic roster had just four players with U.S. college experience. Its 2018 roster had 21 such players.

Ben Smith, who resigned as Northeastern University men’s coach in 1996 to take over the U.S. Women’s National Team as it readied for Nagano, thinks the familiarity with each other that U.S. and Canadian players now gain in college has tamped down to a degree the rivalry between the two countries.

In the lead-up to the 1998 Olympics, when the two women’s hockey powers played 13 exhibition games prior to Nagano, the rivalry burned hot – and hotter.

The U.S. had lost to Canada in the final of the first four World Women’s Championships, but it took overtime for Canada to win worlds on home ice in April 1997. Canada suddenly found itself with a strong challenger, as the exhibition games made clearer, with Team USA winning six and Canada seven.

“They were at the top, and we were trying to encroach on that plateau,” Smith said. “Playing so many times was great for preparation and a recipe for disliking each other. On good days, it got spirited. On bad days, it was ugly.”

There would be bad days before the 1998 final.

# # #

The inaugural Olympic women’s ice hockey tournament had just six teams in one group. Before the U.S. played Canada in the fifth and final game of round-robin group play, the two teams were assured of a rematch for the gold medal. The U.S. had outscored its opponents 26-3, Canada had outscored its opponents by 24-5.

Canada took seeming command of the group play game with three unanswered goals in less than four minutes of the third period for a 4-1 lead with barely 14 minutes to play. But the U.S. would score six straight goals in under 12 minutes for a 7-4 win.

“That comeback was a pivotal moment,” Smith said.

On the power play goal that made it 4-3, every U.S. skater on the ice the puck, with captain Cammi Granato, later a Hockey Hall of Famer, ramming it home from the front of the net. That puck movement brought special satisfaction to Smith, who remembered a team that he said could barely catch a cold, let alone a pass, when he took over.

“That was the goal that gave Canada a bit of holy mackerel,” Smith said. “It wasn’t a fluke, and they knew it.”

There would be an incident in the post-game handshake line that Canada tried to turn into motivation for the final. Canada Coach Shannon Miller alleged that U.S. forward Sandra Whyte made a comment about the recently deceased father of Canadian player Danielle Goyette. Whyte admitted to making a heated remark but denied saying anything about Goyette’s father.

Three days later, when the two teams met again for the gold, Whyte’s Nagano roommate, Sarah Tueting, would get the start in goal. Tueting knew Whyte well enough to be sure she had not crossed any lines, and the goalie wrote off Miller’s allegation as a psychological ploy.

Tueting, also a talented cellist, had come from Dartmouth College to the Olympics with what she recently called “naïve excitement.”

“We were a very tight team, and we were all so innocent in a beautiful way,” Tueting said. “It was a mix of, `OK, I have a job to do, so it doesn’t matter if the Olympic Rings are on the ice,’ and `Oh my God, we’re at the Olympics in Japan!’ ”

Tueting, whose play in goal had helped her high school boys’ team with an Illinois state title, shared net time at the Nagano Games with Sara DeCosta. The team had no goalie coach, so the goalies coached each other, a selflessness rare in two athletes competing for the same position. In the locker room before the final, DeCosta came to Tueting with the “guardian angel” good luck pin DeCosta’s parents had given her before the pre-Olympic tour. DeCosta pinned it onto a back strap of Tueting’s chest protector.

The United States took a 2-0 lead, with Whyte assisting on both scores, before Goyette’s goal made it 2-1 with four agonizing minutes to play. Tueting, who had 21 saves, made the biggest with her right leg 70 seconds from the end. Canada pulled its goalie. Whyte then scored into an empty net with eight seconds left, and the full impact of what the team had accomplished began to smack them, with a joyous, wacky celebration soon to follow.

“Oh my god, this is going to happen,” Ruggiero remembers thinking after Whyte’s goal.

Smith would get extra pleasure from the win, knowing it meant the U.S. had also taken the season series from Canada, 8-7. “We were keeping track, and I’m sure they were, too,” he said.

Once the Medal Ceremony ended, the U.S. players had no idea about how – or if – their triumph would play back home. The game had begun at 4 a.m. Eastern and 1 a.m. Pacific. In an era well before social media, players’ contact with people outside Nagano came only from emails they could read at an Internet café, the “Surf Shack,” in the Olympic Village.

Those emails made it clear how many people these pioneers had touched. Tueting remembers little girls writing her to say, “Now I can play hockey!” and mothers writing her to say, “This was never an option for me, but it can be for my daughter.”

Kendall Coyne was one of those little girls. She had never found another girl who played hockey until, at age seven, she went to Granato’s suburban Chicago hockey camp in the summer of 1998. There she found about 100 other girls on the ice, defying the kids in Coyne’s elementary school who had told her, “Girls don’t play hockey.’’’

“I was so excited to go back to school and tell all my friends girls really do play hockey,” said Coyne, now Coyne Schofield. “That moment at camp fueled me to do something that would change my life forever – play in college, represent Team USA, play in The Olympics.”

Coyne would do all that, winning a gold medal in 2018. Last season, she became the first woman to compete in the skills’ competition at the NHL All-Star Game, with a time in the fastest skater event less than a second slower than that of the winner, superstar Connor McDavid. She also is a member of the San Jose Sharks TV broadcast team and an analyst for the NHL Network.

And Coyne’s own hockey camp will take place for the fifth straight year this summer.

“Cammi was so accessible to me as a kid,” Coyne said. “I knew I had to be accessible to the next generation.”

The captains of the 2018 U.S. Olympic Team, the next generation, asked their gilded ancestors to write letters to the 2018 players before the Winter Games in South Korea. Tueting’s was addressed to the three goalies. She crafted part of it as a letter to her “younger self” heading to Nagano.

“And then,” Tueting concluded, “maybe twenty years from now, you’ll be sitting on a plane writing a letter to three goalies heading to The Olympics to backstop their team to their own gold medals. I sure hope we get to see their medals at some point.”

In those 2018 medals, in all future medals, the women of the Nagano 1998 Olympic Winter Games champions can see themselves. Every women’s hockey team that follows them is a reflection of this U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Hall of Fame team’s contribution to women in their sport.

Philip Hersh, formerly Olympic specialist for the Chicago Tribune, has covered 19 Olympic Games.