Candace Cable did not like competition or confrontation as a youngster; she eventually became a nine-time Paralympian and 12-time Paralympic medalist.

By Josh Barr

Growing up in Southern California, Candace Cable was the furthest thing from an athlete.

“Not at all!” she said. “I didn’t even like going to physical education [in high school]. I did not like being involved in competitive sports. I didn’t like confrontation. I didn’t like the idea of trying to beat someone or having winners.”

That’s not to say, however, that Cable did not enjoy sports.

Cable did like the social component that a sports team provided, so she joined a friend as scorekeepers for their high school basketball and wrestling teams. Her father, Lewis, loved watching the Olympics on television and often was joined by the family. And the entire family enjoyed being outdoors for recreational activities; two-week family vacations usually “revolved around something with water,” Cable said.

But how did the girl who didn’t like the thought of there being winners or losers somehow become one of the world’s elite athletes?

How did that girl, who might say, “I’m sorry,” for hitting a winner when playing tennis with a friend, evolve into a three-sport Paralympian?

It started with a life-changing accident that resulted in Cable being paralyzed from the waist down, then included six months in a hospital and a bout with depression and finally, as Cable said, “finding her people.” Through all of that, Cable emerged not only as the person who would soon become a nine-time Paralympian and 12-time Paralympic medalist, but also as a courageous leader who would make an impact as a leading activist for the civil and human rights of disabled people.

Following high school, Cable had moved to Lake Tahoe, California and become a blackjack dealer. But two years later, at age 21, she was a passenger in a car crash that injured her spinal cord and forever altered her life.

“After six months in the hospital, I honestly thought I was going to spend the rest of my life in a nursing home or something like that,” Cable said. “I couldn’t imagine using a wheelchair for mobility, I’d never seen someone like me. Through extensive psychotherapy, group therapy, all kinds of therapy, I went to try to figure out how not to be sad and angry and depressed about my spinal cord injury.”

Therapy helped and when complete, Cable enrolled at Long Beach State University. There, she wanted to be involved in a social circle with other disabled students.

“Some of them did sports, so I said, ‘I guess I’ll do these sports too,” Cable said. “I tried wheelchair tennis, wheelchair basketball. Wheelchair racing was just being invented and I was with the people who were inventing it on the West Coast.

“Not wanting to compete or confront got overrode by the desire to connect with the community and changing the negative way people saw me and I saw myself.”

The transformation didn’t happen overnight. There were still races where Cable would not see room for her chair to go and it would be many years before the American Disability Act was passed in 1990. But Cable was determined to show that having a disability did not make her – or her peers – any less capable and the world needed to let them in.

Cable qualified for the Arnhem 1980 Paralympic Games, where she won two gold medals and one silver. Eight years later, at the Seoul 1988 Paralympic Games, she won five gold medals. In 1992, Cable made history. She participated in the Paralympic Winter Games in cross-country skiing and downhill skiing, winning one silver medal and two bronze medals at Albertville. Less than six months later, Cable competed in the Summer Paralympic Games in Barcelona, taking gold in the 4×100-meter relay and becoming the first American woman to win medals in Winter and Summer Games.

“Candace was kind of a surprise to us because she wasn’t the athlete type,” said David Kiley, who met Cable at the Rancho Los Amigos rehabilitation facility in Southern California and would go on to be a three-sport Paralympian himself, winning gold medals in each sport. “She found herself in that world and said, ‘Why not?’ She always had this personality and smile that attracted other people – a gentle heart and soul – but inside that fire started to rage over time.

“I saw her enter road racing and track from entry-level to oh-my-god. You look at it 2 ½ to three decades later, hardly anybody has won as much as she has.”

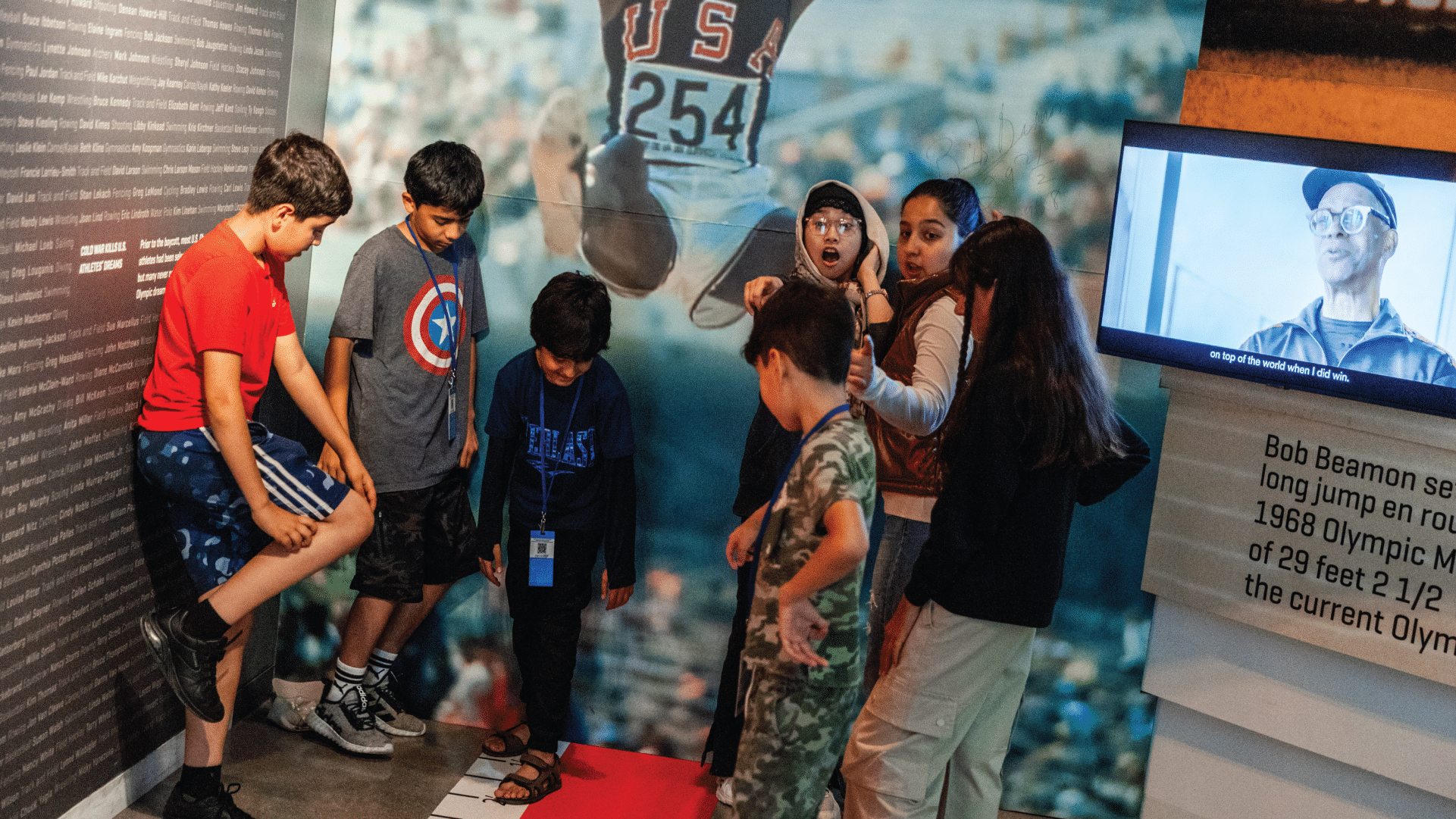

A significant point in Cable’s understanding of her advocacy and how she could use sport in that platform came in 1984 when the Los Angeles Olympic Games held a demonstration event of Paralympic sport during the Olympic track program. The sport of wheelchair racing was chosen, 1,500 meters for men and 800 meters for women and Cable qualified for the women’s event. These events exposed the world to athletes with disabilities, dispelling the negative stereotypes of people with disabilities and expanding the world of sport. Cable took home a bronze medal and – just as importantly — a renewed sense of determination for inclusion.

In addition to becoming an elite racer, the girl who once avoided confrontation at all costs now sought to use her position to fight for change.

On occasion, Cable would use unauthorized equipment in a race in order to demonstrate how progress could be made. If she got disqualified from a race, so be it to progress the sport. Cable laughed about older regulations that for years went unchanged, requiring racing wheelchairs to have handles in the back or prohibiting the steering compensator that created equity and safety in the sport.

Cable and her fellow racers, also pushed to be included in road races, traveling the country to meet with race directors, trying to persuade them to include wheelchair racing divisions in running races. Now running races worldwide have wheelchair divisions.

“There was a group of us that pounded the pavement,” Cable said. “We had to quell a lot of their fears and anxiety about people with disabilities. And to this day, we still have so much to dismantle about what non-disabled falsely believe that people with disabilities can and cannot do. Disability is a human life experience we will all experience.”

“She asks the hard questions,” said Karin Korb, a wheelchair tennis national champion and two-time Paralympian. “When we are on the [U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Athletes Advisory Council] it’s almost like you can see the audience roll their eyes: ‘Oh my god, Candace is asking the question again.’ That is what it takes, asking the poignant question that nobody wants to discuss.

“She has this cadence when she speaks, she draws you into the conversation and it’s very curious and very unassuming and then she asks the question and she raises the bar and has a reciprocal expectation of you that you’re going to step into that space with her, either willingly or with reluctance. She will say the thing that everyone in the room is thinking but will never say, because she is fearless and that’s what creates change.”

But as much as Cable embraced her athletic self, she remained true to who she was. When she crossed the line – off the track, off the road, off the path, off the hill – she was back to being herself.

“I knew when I was done with a race, that was the race and now we’re in the social piece and can hang out and be friends. There were some people who didn’t make that transition and that’s okay too,” Cable said. “When I started competing, one of the ways I was going to be non-confrontational was, ‘I’m not competing against other people, I’m competing with myself.’ I have friends who say I was two different people, when I was in a race and not in a race. What I discovered about myself, in this life race, is that I enjoy teaching and elevating people with inclusive knowledge and experience and that I can live with all the time.”

Josh Barr was a sportswriter at The Washington Post for 17 years.