Tim Nugent made an impact far and wide as one of the leading advocates for people with disability.

By Craig Chamberlain

Tim Nugent was a visionary who changed the world for people with disabilities, considered by many the “father of accessibility.”

Part of Nugent’s legacy is in the hundreds of elite para-athletes who have flowed from the university program he first developed, but his influence went well beyond that.

In 1948, that program was a new experiment in higher education for those with physical disabilities, starting with wounded veterans of World War II. The site was a former hospital on a short-lived University of Illinois satellite campus in Galesburg, Illinois.

Nugent was a 24-year-old war veteran and a University of Wisconsin doctoral student who had been an avid athlete and knew the value of sports in his own life. “I figured it could do the same things for these kids, and it did,” he said.

“Where other people saw invalids who would forever be relegated to a position on a porch, watching life go by, Tim saw future corporate leaders, scientists, educators, lawyers, doctors and international athletes,” said Brad Hedrick, once a doctoral student in Nugent’s program and later its director, speaking at the time of Nugent’s death. “I don’t know how to state how unimaginably incredible that vision was.”

# # #

Born with a “bad heart,” Nugent in 2014 said doctors had his mother “scared to death” that he should avoid strenuous activity. “She wanted me not to do this, not to do that. But I wanted to play, wanted to be with the kids.”

He overcame the condition and in high school played football and basketball, and participated in track. “That was my social life, that was my method of achievement and recognition; it was everything to me at that time,” he said.

In college and the military, during and after the war, Nugent continued to play the same sports and often coached them as well.

Other aspects of his early life also likely motivated his career.

Nugent’s father, a successful businessman, was nearly blind and deaf. And Nugent saw a younger, talented sister go downhill psychologically when eye problems caused a doctor to restrict her activities.

His family also moved frequently within and around Milwaukee’s various ethnic neighborhoods, which helped him learn to respect a variety of people, he said.

Before Nugent’s service in World War II, he studied health and physical education with plans for medical school. He served as an Army medical corps instructor before being shipped to Europe in an infantry division.

It was his athletic skills and not his medical training, however, that would determine his role in combat. His company commander saw Nugent’s speed at an infantry track meet and made Nugent the company runner, where he was called on to carry messages between units or run lines for communication.

He then served as an athletics and recreation officer in Europe after the war, where he coached and supervised events and refereed in a military championship.

When Nugent took charge of the Illinois program three years after the war, however, sports generally was not part of life for people with disabilities. Neither was independence or opportunity. Little was expected. Those with spinal injuries were restricted mostly to their homes, nursing homes or hospitals. Few worked or thought about college. Doctors often were overprotective and predicted they would live short lives.

Nugent sought almost immediately to change those attitudes and circumstances, and sports was part of it. “I knew after a month that these guys needed something else, something to give vent to their emotions, something to give them personal satisfaction, (a sense) of mastering a skill,” he said.

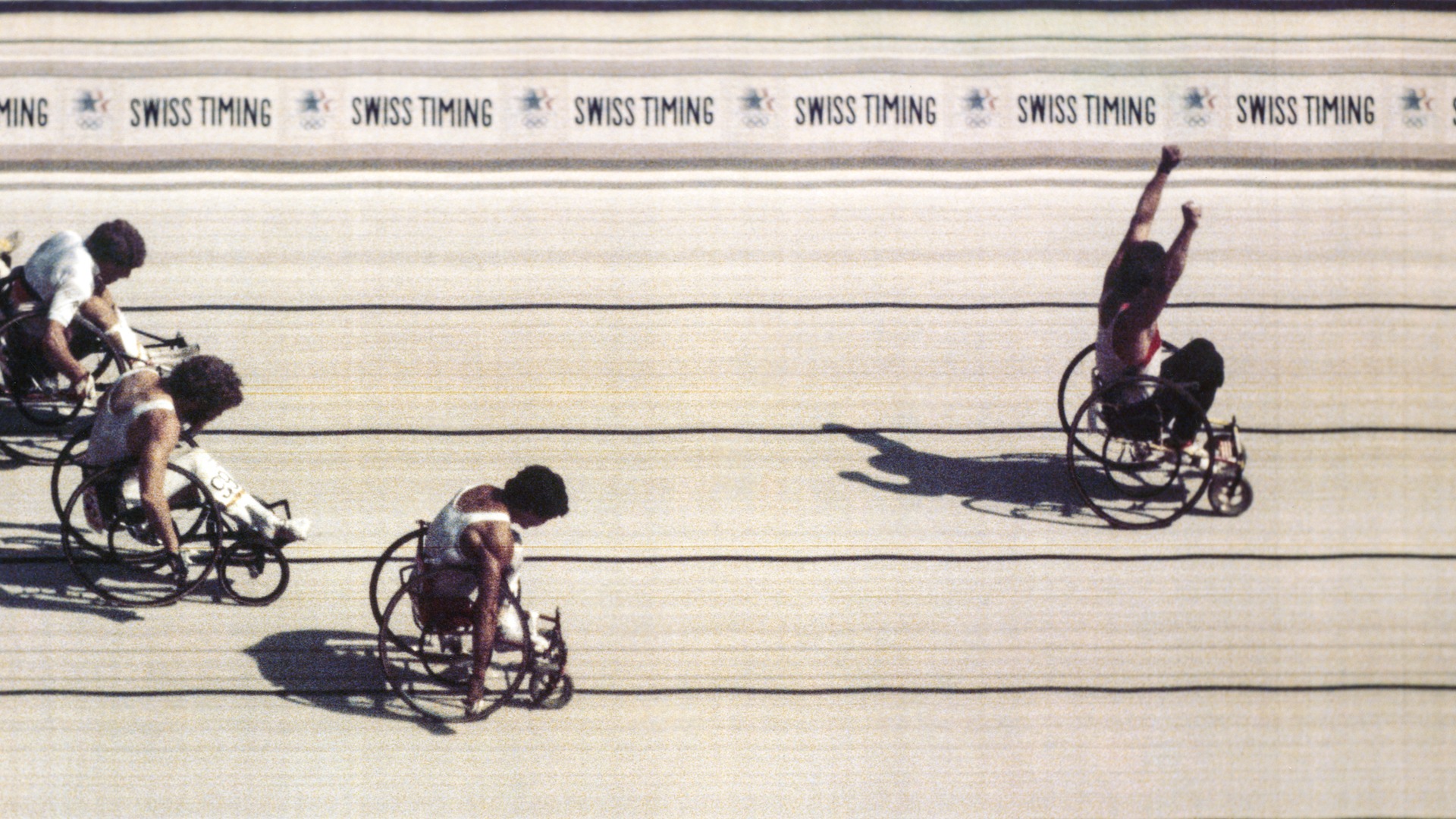

What followed was wheelchair bowling, swimming, basketball, football, baseball. “As one was successful, we added another one,” he said.

Wheelchair basketball was starting up at different places, with some of the teams based at Veterans Administration hospitals. In spring 1949, the Galesburg campus hosted the first National Wheelchair Basketball Tournament, with Nugent’s Gizz Kids one of six teams – the only one associated with a school.

From this came the founding of the National Wheelchair Basketball Association, with Nugent as its first commissioner.

Sports played another role as well – in changing attitudes. Nugent and his wheelchair athletes took their games and exhibitions on the road to high school and college gyms, getting the program exposure and raising money to support it.

But they also were “conveying a message,” Nugent said, starting with player introductions, which made note of students’ majors and future plans. They conveyed another message in the way they played.

“(Spectators) would see these kids fight with each other, I mean really scrap,” he said. “They would see them get mad at the official; they would see the normalcy of their attitudes and their ambitions and their desires, as well as their skill, which was unbelievable.”

Nugent died at 92 on Veterans Day, Nov. 11, 2015, but in the year before that he spoke in great detail about other aspects of establishing what is now the Division of Disability Resources and Educational Services at Illinois, first in Galesburg and then a year later on the flagship campus at Urbana-Champaign. It was the first comprehensive service program serving students with disabilities attending college, and remains one of the most extensive full-service programs today.

Describing those years, Nugent didn’t talk about any great vision or plan, but rather about a progression of events, of different problems requiring different solutions. “The presence of a problem is the absence of an idea” became the mantra he later drilled into his students.

Nugent had free rein to shape things and he did, though not without resistance. A driving force, he was called a maverick, a radical, a troublemaker. Other times, worse. In a variety of ways, he challenged conventional wisdom and attitudes – about what people with disabilities could do, where they belonged, who they were.

Among his initiatives was a training program for new students that taught them practical skills for dealing with daily needs and for navigating the campus and coursework. “Nugent’s boot camp,” it was called. Or “hell week.” He encouraged parents to stay away until students were acclimated. He made sure that students in the program were the ones running a new rehabilitation service fraternity.

Nugent had to battle not only for funding, especially in the early years, but often in getting the accommodations his students needed: adding ramps to building entrances, installing curb cuts on key sidewalks, shifting classes to rooms that were more accessible, gaining access to gyms, establishing the first fixed-route accessible bus system on a college campus.

Even while Nugent and his staff worked to develop the campus program, they were initiating and supervising research that would have an effect well beyond it.

One example was the “ramp that led to nowhere,” a testing ramp built on campus that could be adjusted as researchers determined how steep a ramp should be and what materials provided the best traction for persons with varying degrees of disability. Other research dealt with aspects of building design and accessibility. Nugent played a leading role on the committee that in 1961 issued national standards for making buildings accessible and usable by people with physical disabilities.

Research from the program also laid the groundwork for later legislation, from the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. And some credit the program as being the birthplace of the disability rights movement.

Sir Philip Craven, president of the International Paralympic Committee at the time of Nugent’s death, noted that he “was a true pioneer not just for para-sport … he also strongly believed in nurturing the whole person to help them reach their full potential.” He compared Nugent’s impact in the U.S. to that of Sir Ludwig Guttmann of Great Britain, considered the father of the Paralympic Movement.

Para-athletes with connections to the program Nugent established have won hundreds of medals in the Paralympics and continue to make a mark. Jean Driscoll and Tatyana McFadden have set the standard for women’s wheelchair marathons, with Driscoll already in the Hall of Fame and McFadden still setting new records in her wake. Daniel Romanchuk recently won his second straight Chicago Marathon in the men’s wheelchair division, combined with victories in New York City, Boston and London.

It’s a different world from seven decades ago when Nugent first began to change attitudes about people with disabilities, their ability to be independent and how to make the world most accessible – with athletics as a key component.

“He forever changed the trajectory of the lives of people with disabilities everywhere,” Hedrick said.

Craig Chamberlain is an editor and writer at the University of Illinois News Bureau.